The Panama

The Panama, the last ship carrying Mayo orphan girls, departed from Plymouth on 6 October 1849 and arrived in Sydney on 12 January 1850, with 157 orphans in total from Dublin, Carlow, Clare, Cork, Galway, Kilkenny, Mayo, Sligo, Waterford, and Wexford.

Records indicate that 90 Mayo orphan girls were on the Panama to Sydney, however at this stage the confirmed list only contains 85 names.

The Mayo girls on the Panama were from the four Mayo workhouses that participated in the Emigration Scheme. Ballina sent 40 girls, Ballinrobe sent 25, Castlebar sent 15, and Westport sent 10 girls. Click here to access the complete list of names.

Records indicate that 90 Mayo orphan girls were on the Panama to Sydney, however at this stage the confirmed list only contains 85 names.

The Mayo girls on the Panama were from the four Mayo workhouses that participated in the Emigration Scheme. Ballina sent 40 girls, Ballinrobe sent 25, Castlebar sent 15, and Westport sent 10 girls. Click here to access the complete list of names.

Newspaper Records

The Mayo Constitution (25 August 1849) recorded the visit of the Emigration Agent, Lieutenant Henry, to the workhouses of Co Mayo to choose orphan girls from each union who would eventually proceed on the Panama to Sydney. This was his second visit to the county, and the first to all four workhouses.

The newspaper notes that at Westport workhouse, where ten were eventually chosen to emigrate, “but one young girl could even read and she was educated at Achill colony”. Henry, according to the newspaper, expressed surprise that “education should be hidden from such intelligent persons as the Westport paupers seemed to be”.

The Mayo Constitution (25 August 1849) recorded the visit of the Emigration Agent, Lieutenant Henry, to the workhouses of Co Mayo to choose orphan girls from each union who would eventually proceed on the Panama to Sydney. This was his second visit to the county, and the first to all four workhouses.

The newspaper notes that at Westport workhouse, where ten were eventually chosen to emigrate, “but one young girl could even read and she was educated at Achill colony”. Henry, according to the newspaper, expressed surprise that “education should be hidden from such intelligent persons as the Westport paupers seemed to be”.

|

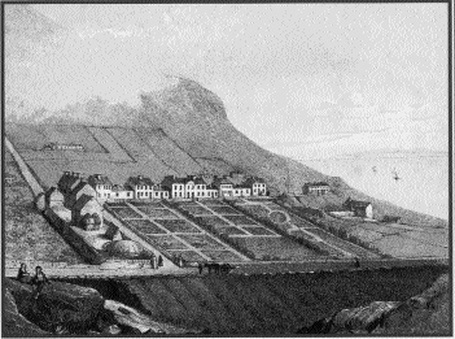

The information revealed about "Achill colony" in this short article is significant. The Achill Island Mission, or ‘Achill Colony’, near Dugort on Achill Island, was founded by Edward Nangle in 1834, with the main aim of converting the island inhabitants to the Protestant faith. More information on the Achill Island Mission can be found on the History Ireland website here.

The Westport Union Board of Guardian minutes, discussed here, note that two girls from the Westport workhouse were from Achill: Mary McNamara and Bridget MacNamara. The Shipping List for the Panama reveals that, despite the difference in the spelling of the surname in the Minute Book, it is most likely that girls were sisters; their parents, both dead, were Thomas and Honora. It can therefore be assumed that it was Mary, age 18, who was educated at “Achill colony”, as the Shipping List records her religion as Church of England, whereas Bridget, age 19, is recorded as being Roman Catholic. What could have been perceived as an error in the Shipping List in the recording of Mary’s religion, in fact appears to reveal that she converted to the Protestant faith during her time at Achill Colony. |

The Ballina Chronicle also reported the visit of the Emigration Agent, Lieutenant Henry. In an editorial on 29 August 1849 on the subject of “Emigration to the Colonies”, the writer describes sending “some of the youngest and healthiest of our superabundant pauper population”. The paper reports of “the anxiety which they [the girls] manifest to rescue themselves from a state of pauperism and dependence”.

This is the first of a few occasions where the newspapers refer to the willingness of the girls to avail of the Orphan Emigration Scheme. The Mayo Constitution (18 and 25 September 1849) records the departure of girls from Castlebar and Ballinrobe workhouses, and the Ballinrobe correspondent maintains that “there are many more paupers in the house who would gladly emigrate to the same place, and on the same terms, if they could”.

In terms of this willingness of girls to emigrate, an article three years later (8 September 1852) in the Connaught Telegraph is significant. The article describes a petition from the “young female paupers” to the Earl of Lucan and the Board of Guardians of Castlebar workhouse:

“The Petition of Twenty-five Pauper Girls from the age of 16 to 25 years – humbly sheweth –

“That we are, and have been, in the Workhouse for years; that we have no friends to help us, and that we have grown from girlhood to womanhood within these walls, and that being too young when the Emigrants were going hence to Australia in the year 1849, we were debarred the only hope that we could have in this world of bettering our condition…”

The girls declare that they “are obliged to remain in the poorhouse, not from choice, but for protection”, and ask the Board of Guardians, “the only protectors we have in the world”, to send them “to some country where we can have the blessing of becoming useful and not dependent members of society”. The petition is concluded with a list of names of the girls:

Ellen Walsh, Mary Curren, Catherine Fletcher, Biddy Murphy, Ellen McDermott, Kitty Walsh, Kitty Farrell, Honor Malley, Mary Flynn, Mary Bourke, Mary Malley, Mary Flynn, Biddy Woods, Maria Pinkerton, Mary Morrison, Ellen Murphy, Anne Walsh, Maria Grady, Biddy Munnelly, Mary Carron, Honor Christy, Honor Dolan, Mary Talley, Honor Flynn, Jane McManmon, Maria Bourke, Mary Mulhearn, Honor Vahey, Ellen Nolan, and Anne Hadden

This is the first of a few occasions where the newspapers refer to the willingness of the girls to avail of the Orphan Emigration Scheme. The Mayo Constitution (18 and 25 September 1849) records the departure of girls from Castlebar and Ballinrobe workhouses, and the Ballinrobe correspondent maintains that “there are many more paupers in the house who would gladly emigrate to the same place, and on the same terms, if they could”.

In terms of this willingness of girls to emigrate, an article three years later (8 September 1852) in the Connaught Telegraph is significant. The article describes a petition from the “young female paupers” to the Earl of Lucan and the Board of Guardians of Castlebar workhouse:

“The Petition of Twenty-five Pauper Girls from the age of 16 to 25 years – humbly sheweth –

“That we are, and have been, in the Workhouse for years; that we have no friends to help us, and that we have grown from girlhood to womanhood within these walls, and that being too young when the Emigrants were going hence to Australia in the year 1849, we were debarred the only hope that we could have in this world of bettering our condition…”

The girls declare that they “are obliged to remain in the poorhouse, not from choice, but for protection”, and ask the Board of Guardians, “the only protectors we have in the world”, to send them “to some country where we can have the blessing of becoming useful and not dependent members of society”. The petition is concluded with a list of names of the girls:

Ellen Walsh, Mary Curren, Catherine Fletcher, Biddy Murphy, Ellen McDermott, Kitty Walsh, Kitty Farrell, Honor Malley, Mary Flynn, Mary Bourke, Mary Malley, Mary Flynn, Biddy Woods, Maria Pinkerton, Mary Morrison, Ellen Murphy, Anne Walsh, Maria Grady, Biddy Munnelly, Mary Carron, Honor Christy, Honor Dolan, Mary Talley, Honor Flynn, Jane McManmon, Maria Bourke, Mary Mulhearn, Honor Vahey, Ellen Nolan, and Anne Hadden

Almost two years after the Mayo girls left on the Panama, the Connaught Telegraph (20 August 1851) recorded a letter received by “the Rev. Mr. Cavanagh, R.C.C., Westport”. The writer was “one of the female emigrants from the Poorhouse there to the Australian Colony”, and that:

“The account given by the writer of the happiness enjoyed by her and her female companions, as also by the females sent thither from the Castlebar Workhouse, is, we understand, of a most cheering nature”.

The article goes on to say, “We hope to be enabled to publish the letter next week”. However, frustratingly, no trace of this letter ever being published could be found.

“The account given by the writer of the happiness enjoyed by her and her female companions, as also by the females sent thither from the Castlebar Workhouse, is, we understand, of a most cheering nature”.

The article goes on to say, “We hope to be enabled to publish the letter next week”. However, frustratingly, no trace of this letter ever being published could be found.

© Barbara Barclay (2015)